When Chromosome 15 Duplicates: A Clinical-Genetic Challenge

Authors

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.37980/im.journal.ggcl.en.20252717Keywords:

Dup15q syndrome, Chromosome 15q11-q13, Array-CGH, Autism spectrum disorder, EpilepsyAbstract

Background: Chromosome 15q11–q13 duplication syndrome (Dup15q) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder caused by additional copies of a genomic region enriched in imprinted genes essential for normal neuronal function. It is commonly associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), epilepsy, hypotonia, global developmental delay, and intellectual disability. Case presentation: We report the case of a 31-year-old male with a longstanding history of refractory epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and intellectual disability. Genetic evaluation using array-comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH) combined with single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis identified a de novo interstitial heterozygous duplication of 10.03 Mb involving the 15q11.2–q13.3 region. The duplicated segment encompasses multiple genes with key roles in neurodevelopment, including UBE3A, GABRB3, GABRA5, SNRPN, and NDN. Parental testing by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) was negative, confirming a non-inherited origin. Establishing the molecular diagnosis allowed precise clinical classification, informed therapeutic decision-making, and enabled appropriate genetic counseling. Conclusion: This case illustrates the diagnostic value of array-CGH in patients with complex neurodevelopmental phenotypes and emphasizes the importance of early genetic assessment in individuals presenting with ASD and epilepsy. Identification of pathogenic copy number variants such as Dup15q has significant implications for prognosis, clinical management, and family counseling.

Introduction

15q11.2–q13.3 duplication syndrome (Dup15q) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder with autosomal dominant inheritance caused by duplication of the chromosomal segment 15q11.2–q13.3. This region, located on the long arm of chromosome 15, is highly susceptible to recombination errors during meiosis due to the presence of low-copy repeat sequences (LCRs). These structural anomalies arise primarily through non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) between specific breakpoint regions (BP1 to BP5) [1].

The duplication may occur in two main forms: as an interstitial duplication on the maternal chromosome 15 or as a supernumerary isodicentric chromosome [idic(15)], which involves two additional copies of the duplicated region. These variants confer variable clinical expressivity and incomplete penetrance; some carriers may be asymptomatic or present with a mild phenotype. Maternal-origin duplications have been associated with more severe clinical manifestations compared to paternal-origin ones [1].

From a pathophysiological perspective, it has been proposed that the gene dosage imbalance caused by the duplication contributes to pathological overexpression of genes critical to brain development. This phenomenon may interfere with synaptic maturation, neuronal plasticity, and ion channel regulation—processes essential for proper central nervous system function. These neurobiological alterations underlie the hallmark signs and symptoms of the syndrome [2].

Clinically, Dup15q presents with a wide range of symptoms, including global developmental delay, intellectual disability, neonatal hypotonia, language and motor skill deficits, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and drug-resistant epilepsy, the latter being associated with an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Epilepsy is among the most disabling manifestations, affecting over 60% of patients and often presenting with polymorphic seizures that may evolve toward a Lennox–Gastaut–like phenotype. Electroencephalographic findings may include focal spikes, generalized spikes, diffuse fast rhythms, and hypsarrhythmia. Mild dysmorphic features such as an upturned nose, epicanthal folds, and downslanting palpebral fissures may also be observed [1–5].

Diagnosis begins with a high index of clinical suspicion upon recognition of these signs. Due to phenotypic overlap with other genetic disorders such as Angelman syndrome or Prader–Willi syndrome, high-resolution genetic tools are required to confirm the diagnosis. Chromosomal microarray or comparative genomic hybridization (CMA or array-CGH) is considered the first-line test, as it allows detection of submicroscopic duplications and provides precise localization and sizing of the abnormality. This recommendation has been endorsed by multiple international guidelines, including those from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics [6–10].

Once a duplication is detected, complementary techniques are recommended to determine the underlying mechanism. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and conventional cytogenetic studies can detect the presence of idic(15) chromosomes and identify potential mosaicism. Additionally, MLPA (Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification) is useful for quantifying duplications or triplications in the 15q11.2–q13.3 region. Finally, DNA methylation analysis is essential to determine the parental origin of the duplication, as maternally derived duplications are associated with a more severe clinical phenotype [6,8,11,12].

In terms of treatment, early detection of the duplication allows implementation of personalized interventions aimed at optimizing neurocognitive development and improving management of comorbidities such as refractory epilepsy. Moreover, patient-derived cellular models, such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), have opened new avenues for investigating the molecular mechanisms of Dup15q, with the goal of developing targeted therapies tailored to the specific needs of this population [13].

Case Presentation

The patient is a 31-year-old male evaluated by the genetics service. He was born to a 34-year-old mother and a 35-year-old father at the time of conception. The mother had a history of one prior spontaneous abortion. The pregnancy occurred without known exposure to teratogenic agents. Delivery was via cesarean section at 42 weeks of gestation due to post-term pregnancy and was complicated by a nuchal cord, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and clinical signs of perinatal asphyxia. The patient required orotracheal intubation at birth, although no evidence of meconium aspiration was observed.

Parental consanguinity was not reported. The family history revealed two paternal uncles with unspecified epilepsy and a maternal uncle with an unspecified behavioral disorder. There was no documented family history of congenital malformations, genetic disorders, behavioral syndromes, or major psychiatric conditions.

Since early childhood, the patient has exhibited global developmental delay, with complete dependence for basic daily activities. Epileptic seizures began at six years of age, predominantly during sleep, and were characterized by generalized tonic features, sialorrhea, sphincter relaxation, and postictal drowsiness. The frequency and severity of seizures progressively increased, with poor response to multiple antiepileptic drugs, resulting in a clinical picture consistent with refractory epilepsy.

Physical examination revealed no overt facial dysmorphisms. The patient could walk independently with a stable gait, without the need for assistive devices. Limited eye contact was noted, as well as forward-facing ears, absence of verbal language with guttural sound production, hand flapping, and motor stereotypies involving the upper limbs and head. No spinal deformities or limb asymmetries were found. External genitalia were normal; the prepuce was redundant with a constriction ring at the glans level, and both testes were located in the scrotum. Macroorchidism was not observed.

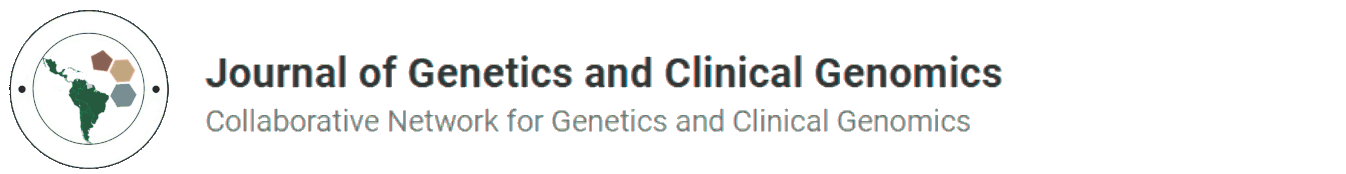

Given the clinical constellation of refractory epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and intellectual disability, a genetic etiology was strongly suspected. Therefore, molecular analysis was conducted using array-based comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH) integrated with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis. The test was performed using the SurePrint G3 Human CGH+SNP 4×180K platform (Agilent Technologies). This methodology enables the simultaneous detection of genomic copy number variations—such as deletions (losses), duplications (gains), and unbalanced chromosomal rearrangements—thus offering high-resolution insight into the genomic architecture underlying neurodevelopmental disorders.

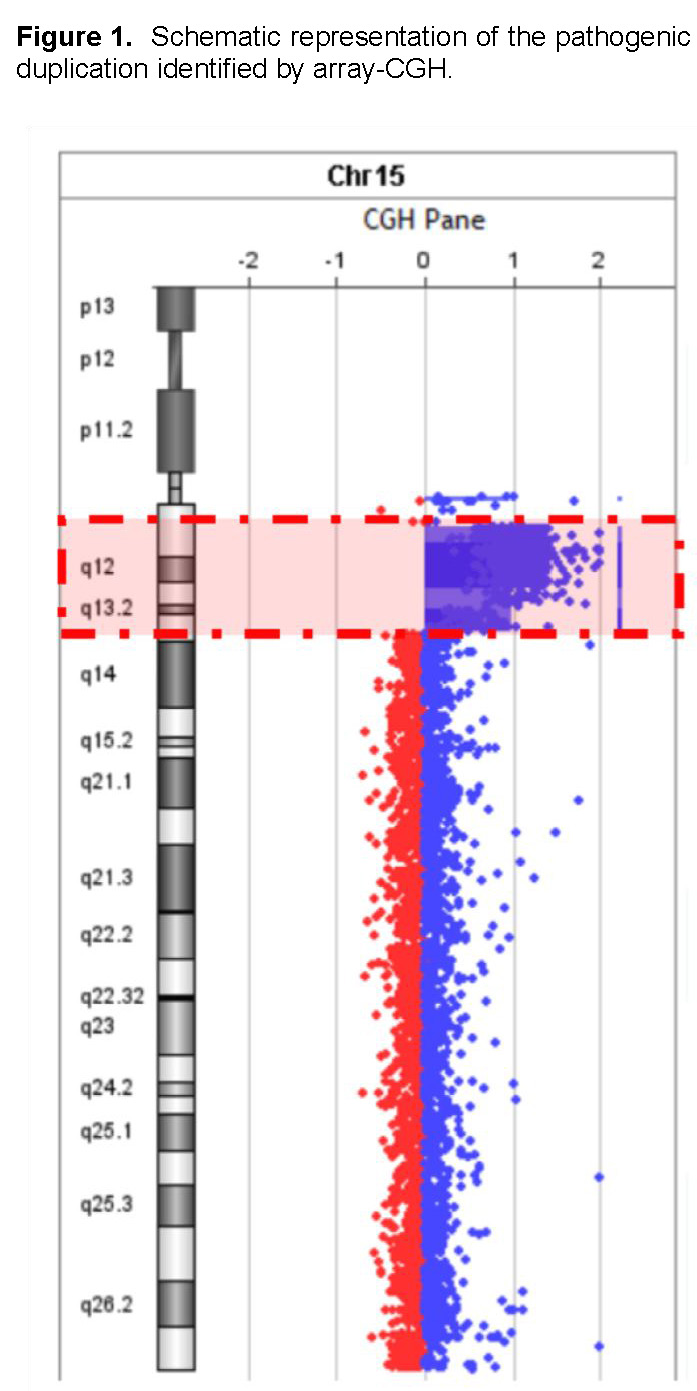

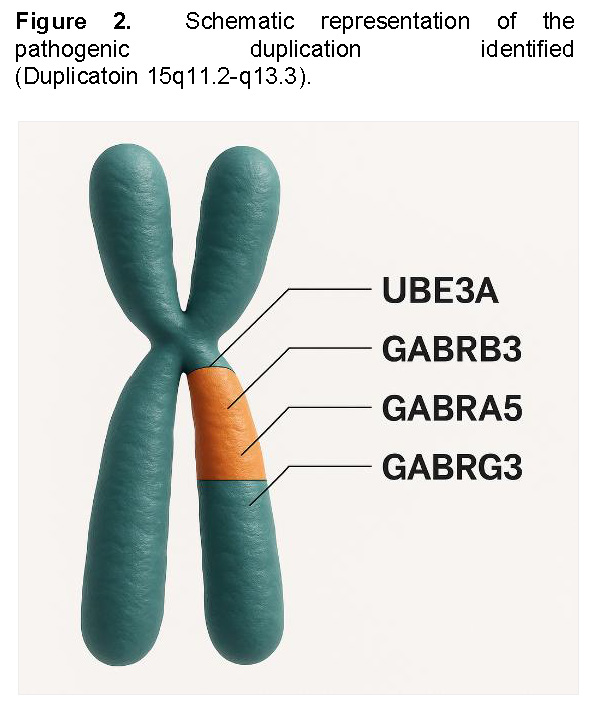

The analysis identified a heterozygous interstitial duplication of 10.03 megabases (Mb) in the 15q11.2–q13.3 region (genomic coordinates chr15:22572809–32607357, GRCh38 reference genome) (Figures 1 and 2). This duplicated segment encompasses several functionally significant genes, including UBE3A, GABRB3, GABRA5, SNRPN, and NDN, all of which play critical roles in neurodevelopment and GABAergic neurotransmission. The 15q11–q13 duplication syndrome (OMIM #608636) has been associated with a spectrum of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, hypotonia, ataxia, seizures, developmental delay, behavioral disturbances, and schizophrenia (PMID: 21324950).

There is growing evidence of a parent-of-origin effect, with maternally inherited duplications more commonly linked to clinical phenotypes. In contrast, paternally derived duplications have been frequently observed in unaffected individuals, although some cases have been documented in patients with autism spectrum disorder (PMID: 23495136) and seizures (PMID: 23633446). However, these findings remain inconsistent, and the current number of reported cases is insufficient to conclusively establish a genotype–phenotype correlation for paternally inherited duplications (PMID: 18840528). Based on American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines, this copy number variant is classified as pathogenic. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the genes according to the Human Phenotype Ontology.

Identification of this duplication confirmed the diagnosis of 15q11–q13 duplication syndrome (Dup15q). To further investigate the genetic origin, targeted MLPA analysis of the 15q11–q13 region was performed in both parents, with negative results. This finding supports a de novo origin of the duplication and confirms a non-inherited genetic etiology, based on the observed correlation between genotype, endotype, and phenotype.

This diagnosis enabled precise clinical classification, informed the therapeutic management strategy, allowed for a more accurate prognosis, and laid the foundation for comprehensive genetic counseling for the family.

Discussion

Current literature on 15q11.2–q13.3 duplication syndrome (Dup15q) highlights the importance of early and accurate genetic diagnosis due to its broad phenotypic spectrum and overlap with other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as Angelman syndrome and Prader–Willi syndrome. In the present case, multiple clinical features—including global developmental delay, hypotonia, refractory epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and mild dysmorphic features—prompted a comprehensive genetic evaluation that led to confirmation of the diagnosis via array-CGH.

This diagnostic approach is consistent with findings by Bisba et al., who recommend chromosomal microarray (CMA) as a first-line test for detecting copy number variations in patients with complex phenotypes. In their study, over 50% of individuals diagnosed with Dup15q presented with intellectual disability, language impairments, and autistic features, all of which were also observed in this patient [1].

Similarly, Rabeya Akter Mim et al., in a cohort of 260 children with neurodevelopmental disorders, found that 3% had pathogenic duplications in the 15q11–q13 region. These cases exhibited comparable clinical profiles, reinforcing the diagnostic value of genetic testing not only as a diagnostic tool but also as a guide for clinical management and family counseling [14].

One of the most challenging aspects of this case was refractory epilepsy, a common finding in Dup15q syndrome. Studies such as Elamin et al. (2023) have proposed a molecular basis for this manifestation, demonstrating alterations in sodium channel inactivation in patient-derived cellular models. This evidence supports the development of targeted therapies, which may offer more effective treatment alternatives in the future [2].

Regarding genetic diagnosis, various authors have advocated for systematic integration of chromosomal microarray (CMA) in the initial evaluation of patients with autism, intellectual disability, and epilepsy [6,10]. In this patient, array-CGH precisely established the underlying etiology, confirming its clinical utility as a high-resolution diagnostic tool. Its ability to detect submicroscopic duplications with high sensitivity enabled accurate identification of the structural alteration responsible for the clinical phenotype, consolidating its role as a cornerstone of modern medical genetics.

Furthermore, Bisba et al. emphasized the importance of methylation analysis to characterize duplications in the 15q11–q13 region, particularly to determine parental origin. This factor is prognostically relevant, as maternal duplications are associated with more severe clinical phenotypes. Although this information was not available in the present case, it remains essential for genetic counseling and family planning [1].

In summary, this clinical case illustrates how detailed clinical evaluation, complemented by molecular diagnostic tools such as array-CGH, enables precise identification of an underlying genetic cause and facilitates comprehensive patient management. The experience described aligns with current literature and underscores the need to promote access to molecular cytogenetic studies in clinical settings with high suspicion of genomic anomalies.

Conclusion

The 15q11.2–q13.3 duplication syndrome represents a diagnostic challenge in pediatrics due to its clinical heterogeneity and phenotypic overlap with other neurodevelopmental disorders. In the present case, the presence of refractory epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, and intellectual disability prompted investigation of an underlying genetic cause, which was confirmed through chromosomal microarray analysis (array-CGH).

Application of this technique enabled identification of a pathogenic submicroscopic duplication in the 15q11.2–q13.3 region, thereby establishing the etiologic diagnosis and facilitating a more targeted clinical approach. Array-CGH proved to be a high-resolution method with significant diagnostic value in patients with complex neurological phenotypes, as it allows precise detection of copy number variations that are undetectable by conventional methods.

This case underscores the need to integrate molecular cytogenetic studies into the initial evaluation of patients with high clinical suspicion, as well as the importance of early diagnosis in guiding therapeutic decisions, anticipating prognosis, and providing appropriate genetic counseling to families. Personalized medicine, grounded in molecular understanding of disease, is becoming a fundamental pillar in the management of neurodevelopmental disorders.

References

[1] Bisba M, Malamaki C, Constantoulakis P, Vittas S. Chromosome 15q11-q13 Duplication Syndrome: A Review of the Literature and 14 New Cases. Genes (Basel). 2024 Oct 1;15(10).

[2] Elamin M, Lemtiri-Chlieh F, Robinson TM, Levine ES. Dysfunctional sodium channel kinetics as a novel epilepsy mechanism in chromosome 15q11-q13 duplication syndrome. Epilepsia. 2023 Sep 1;64(9):2515–27.

[3] Piard J, Philippe C, Marvier M, Beneteau C, Roth V, Valduga M, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of a large family with an interstitial 15q11q13 duplication. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 Aug;152(8):1933–41.

[4] Shehi E, Shah H, Singh A, Pampana VS, Kaur G. The Linkage Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Dup15q Syndrome: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022 Apr 17;

[5] Urraca N, Cleary J, Brewer V, Pivnick EK, Mcvicar K, Thibert RL, et al. The interstitial duplication 15q11.2-q13 syndrome includes autism, mild facial anomalies and a characteristic EEG signature. Autism Research. 2013 Aug;6(4):268–79.

[6] Manickam K, McClain MR, Demmer LA, Biswas S, Kearney HM, Malinowski J, et al. Exome and genome sequencing for pediatric patients with congenital anomalies or intellectual disability: an evidence-based clinical guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genetics in Medicine. 2021 Nov 1;23(11):2029–37.

[7] Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, Biesecker LG, Brothman AR, Carter NP, et al. Consensus Statement: Chromosomal Microarray Is a First-Tier Clinical Diagnostic Test for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities or Congenital Anomalies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010 May 14;86(5):749–64.

[8] Cucinotta F, Lintas C, Tomaiuolo P, Baccarin M, Picinelli C, Castronovo P, et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical impact of chromosomal microarray analysis in autism spectrum disorder. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2023 Aug 1;11(8).

[9] Gürkan H, Atli Eİ, Atli E, Bozatli L, Araz Altay M, Yalçintepe S, et al. Chromosomal microarray analysis in Turkish patients with unexplained developmental delay and intellectual developmental disorders. Noropsikiyatri Arsivi. 2020;57(3):177–91.

[10] Jang W, Kim Y, Han E, Park J, Chae H, Kwon A, et al. Chromosomal microarray analysis as a first-tier clinical diagnostic test in patients with developmental delay/intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, and multiple congenital anomalies: A prospective multicenter study in korea. Ann Lab Med. 2019;39(3):299–310.

[11] Aldosari AN, Aldosari TS. Comprehensive evaluation of the child with global developmental delays or intellectual disability. Vol. 67, Clinical and Experimental Pediatrics. Korean Pediatric Society; 2024. p. 435–46.

[12] Ma Y, Yang R, Yan X, Song X, Zhan F. Genetic analysis and prenatal diagnosis of 15q11-q13 microduplication syndrome. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2025;38(1).

[13] Jeste S, DiStefano C. Can Preclinical Insights Give Us Hope for Effective Treatments for Epilepsy in 15q11-q13 Duplication Syndrome? Vol. 90, Biological Psychiatry. Elsevier Inc.; 2021. p. 735–7.

[14] Mim RA, Soorajkumar A, Kosaji N, Rahman MM, Sarker S, Karuvantevida N, et al. Expanding deep phenotypic spectrum associated with atypical pathogenic structural variations overlapping 15q11–q13 imprinting region. Brain Behav. 2024 Apr 1;14(4).

suscripcion

issnes

eISSN L 3072-9610 (English)

Information

Use of data and Privacy - Digital Adversiting

Infomedic International 2006-2025.